Armed Standoffs With the Government, “Uber Militias,” and Ammon Bundy’s Run to Be Idaho’s Next Governor

For six years now, Josh Thayer has been at war with his next-door neighbor over the location of their property lines in Salem, a small town in Utah. Thayer has been prosecuted for trespassing and cited for keeping chickens on his property. He has accused the neighbor of various transgressions, a dispute memorialized in restraining orders, plus a lawsuit and an appeal—both of which Thayer lost. City officials, he claims, have conspired to steal his land so they can give it to well-connected developers. And these days in the West, when you think the government is trying to steal your land, there’s one person you call: Ammon Bundy.

Bundy, 45, is one of the 13 children of Cliven Bundy, a devout Mormon who in 2014 organized an armed standoff against the federal Bureau of Land Management (BLM) at his ranch in Bunkerville, Nevada, where his family had been grazing cattle on public land for more than 60 years. Cliven had stopped paying federal grazing fees in 1993 to protest new environmental restrictions. After a federal judge ordered the cattle removed, the Bundy family, supported by armed militia groups, confronted BLM agents, who ultimately retreated to avoid a bloodbath. The drama played out nightly on Hannity.

The successful standoff turned Ammon into an instant star in the anti–public land firmament, especially after law enforcement failed to arrest any of the Bundys for two years. But the next confrontation would not end so peacefully. In 2016, Ammon traveled to Oregon—claiming the Lord had sent him—where he led a 41-day armed takeover of the Malheur National Wildlife Refuge to protest the reincarceration of two local ranchers who’d been convicted of arson on public land. During the occupation, Bundy’s friend, a rancher named LaVoy Finicum, tried to charge a police blockade. Officers shot Finicum dead as he appeared to reach for his gun, yelling, “Just shoot me!”

Only then were Ammon, Cliven, and several Bundy siblings arrested and charged for their roles in the earlier Nevada standoff. Ammon and his brother Ryan were also charged for the Malheur takeover. But the Lord delivered: An Oregon federal jury stunned observers by acquitting the Bundys. The Nevada case ended in a mistrial after the judge ruled that prosecutors had engaged in “gross misconduct” by improperly withholding evidence from the defense.

The government’s failure to hold the Bundys accountable turned the family into folk heroes in some quarters. After spending two years in jail awaiting trial, upon his release, Ammon became a headliner on the “patriot” speaking circuit, and people all over the West invited him—and the militia groups in his orbit—to parachute into their local land conflicts. His popularity only grew after he mobilized his followers to oppose pandemic restrictions and covid vaccinations. In a timely merger of far-right extremism and Republican politics, Bundy has even leveraged his outlaw celebrity into a campaign for governor of Idaho.

The notion that Bundy, whose critics jokingly deride as the leader of “Y’all Qaeda,” might stand a chance in a statewide election would strike many Americans as absurd. Then again, nobody ever thought Donald Trump would be president. “[Bundy] has this arm reaching really far to the right, to the real extreme kind of militia groups, but he is always careful to position himself as nonviolent,” says James Skillen, a Calvin University professor and author of This Land Is My Land: Rebellion in the West. Bundy’s politics are extreme, Skillen says, but he speaks a language that appeals to mainstream conservatives, Trumpians, and libertarians, as well as Mormons and evangelical Christians. “He’s a meaningful link between mainstream and extreme conservativism in America.”

Win or lose, Bundy’s activism has consequences that extend well beyond Idaho. In late 2019, he formed an organization called People’s Rights, which now claims more than 60,000 members nationally. Dubbed “Ammon’s Army” by the Institute for Research and Education on Human Rights, a nonprofit watchdog that monitors far-right extremism, People’s Rights is rooted in what IREHR President Devin Burghart calls “middle-American neighborhood nationalism”—the idea that the only way to fight government tyranny is to stand with your neighbors to defend your constitutional rights. “For Bundy that goes farther,” Burghart told me. “It’s not just about neighbors but that battle between the righteous and the wicked.”

The Los Angeles Times has described People’s Rights as Uber for militias, a platform Bundy created that enables anyone with a beef against the government to dial up an armed protest on demand. Encrypted Signal messages allow members to communicate and rally each other to action in an entirely decentralized way, sort of like a 21st-century phone tree. Local People’s Rights groups also hold ham radio trainings and food canning lessons to prepare for the apocalypse—or, more likely, if they are deplatformed. “Our goal is so that anybody in People’s Rights can call, and if it is warranted, at least 10 people will show up in 10 minutes, and 100 people show up in 100 minutes, 1,000 people in 1,000 minutes, and so on and so forth,” Bundy told me in an interview in March.

That’s how it worked for Thayer. When he sent out his distress call this past February, dozens of members flocked to Salem. They made harassing calls to the police chief, circulated videos of their menacing confrontations with the mayor, and generally made nuisances of themselves.

Bundy inspires and facilitates these armed flash mobs, and experts I spoke with believe it’s only a matter of time before one turns violent. Climate-driven droughts, wildfires, and extreme temperatures are creating new battles over scarce public resources, particularly if the Biden administration starts enforcing the environmental and land regulations that Trump’s people ignored or deliberately weakened. “You can’t go around waving guns as a political statement and expect no one to get hurt,” Skillen told me. “That’s just not rational.”

Ammon Bundy signing autographs as he throws himself into retail politics while campaigning for governor.

Russel Albert Daniels

Every iconic far-right extremist has a mythic origin story, and Ammon Bundy is no exception. Here’s a short version:

Until 2014, Bundy was just another law-abiding businessman—a devoted Latter-Day Saint raising a big family in Arizona and living the American Dream—until the federal government swooped in and attacked his ancestral home, threatening to turn it into the next Ruby Ridge or Waco. He answered the call to defend his family, and with God’s help, they prevailed over the oppressive forces of the federal government. “My family’s ranch was put under siege and our lives were threatened by federal agents,” he told a Utah audience recently. “Our crime, I guess, was just doing what our family has done for 140 years, which is ranching in the southern Nevada desert.”

The longer version is more complicated.

The Bundy clan likes to suggest they’ve been ranching in Bunkerville since the 1890s, though they actually spent decades bouncing between Mexico and the Arizona Strip, a northwest corner of the state with a punishing desert climate that was settled by Mormons fleeing persecution. Cliven’s father didn’t start grazing cattle near Bunkerville until 1949, and the operation was so barely profitable that Cliven encouraged his children to make their livings elsewhere.

Grazing restrictions, environmental regulations, and Las Vegas sprawl threatened the family’s hardscrabble existence and fueled their distrust for the federal government—as did open-air nuclear testing in the 1950s, which showered radioactive fallout onto unsuspecting residents living downwind. Cliven’s anti-government convictions ran so deep that he wouldn’t allow his first wife, Jane, to sign the kids up for free school lunch when the ranch was struggling—the kind of conflict that may have contributed to her leaving the family when Ammon was 5. Cliven raised his six kids solo until 1991, when he remarried. (Carol Bundy brought four daughters to the fold; she and Cliven had three more kids together.)

In the late 1980s, inspired by the Sagebrush Rebellion in the West, which challenged federal control over land, Cliven began to insist (wrongly) that the Constitution does not allow the federal government to own land, and thus the BLM had no jurisdiction over where his cows grazed. In 1993, he told the agency he would no longer pay his grazing fees. By 2012, the unpaid fees and fines exceeded $1 million, and a federal judge ordered Bundy’s cows impounded. The BLM’s first enforcement attempt was called off based on concerns about a violent response. In 2014, the BLM tried again.

That March, Cliven summoned his children and friends to do “whatever it takes” to protect the cattle. Ammon says Cliven had asked him to bring food and gear to feed the protesters. That’s when the first spidey sense of divine intervention struck him: He should leave his guns at home. When Ammon got to the ranch armed with nothing but a Leatherman, he says he discovered that the BLM had deployed what looked like 200 officers armed to the teeth. Some had taken up sniper positions around the compound despite FBI threat assessments concluding that Cliven wasn’t likely to be violent. Agents in helicopters joined contract cowboys to round up Cliven’s cows for auction. Things started to go south when officers in tactical gear beat up and arrested Ammon’s brother Dave, who was attempting to photograph some of the BLM armament.

A few days later, Bundy family members, including Cliven’s sister Margaret, obstructed the passage of a truck they suspected held cows that the BLM had killed. (It actually held equipment the Bundys used to water their cattle.) Officers threw Margaret to the ground, and Ammon, who had been dutifully grilling burgers, raced to the scene on an ATV. He confronted the officers, who sicced a dog on him—which he kicked—and fired multiple Taser shots. Ammon endured the assault standing up. Photos show him bleeding through his shirt after pulling out the Taser prongs.

Viral videos of the episode were a siren call to militia groups like the Oath Keepers, whose far-flung members flocked to Bunkerville to defend the Bundys from the jackbooted thugs. People like militia leader Eric Parker—who ran unsuccessfully last year for the Idaho state Senate—took up sniper positions on a highway overpass. The BLM stood down. To this day, Cliven’s cows still graze freely, and he still hasn’t paid his fees.

Bunkerville was mainly Cliven’s show, and Ammon probably wouldn’t be the legend he is today if not for the FBI. When he felt called by God to occupy the Malheur National Wildlife Refuge near Burns, Oregon, few people were crazy enough to join him. It was such an ill-conceived, disorganized affair that even Oath Keepers founder Stewart Rhodes declined Ammon’s call to arms. No more than a dozen militants joined the initial occupation, but the FBI helped fill its ranks: Of the 40 or so people ultimately involved in the takeover, at least 15 were federal informants.

The most important piece of evidence in the subsequent trial of Ammon and his co-defendants on criminal conspiracy charges was a video at the refuge where a man with a French accent, who called himself John Killman, led the militants in firearms training. Under his direction, the occupiers fired hundreds of rounds from semiautomatic weapons into the marshland. Introduced by the prosecutors, the video was a dramatic courtroom visual, but prosecutors had neglected to inform the jury that Killman was in fact a government informant named Fabio Minoggio. Or that the FBI had bought Minoggio a bulletproof vest and paid him to travel to the refuge to offer paramilitary training to the occupiers. In a last-minute twist, defense lawyers subpoenaed Minoggio, and his unveiling helped secure the acquittals that created the legend of Ammon Bundy, untouchable, with God on his side.

Three of Ammon Bundy’s nephews.

Russel Albert Daniels

I first saw Ammon Bundy in person in November 2017, when I went to Las Vegas to cover the trial for his role in the Bunkerville affair. One day after the jury was selected, US District Judge Gloria Navarro held a hearing to reconsider the defendants’ detention. By then, Ammon, Cliven, and Ryan had been in jail for more than 650 days because the government insisted they were too dangerous to await trial at home. Ammon took the stand hoping to convince the judge otherwise.

During the Malheur takeover, Bundy had cut a striking figure at his daily press conferences, the epitome of the rugged individualist with his neatly trimmed beard and uniform of blue plaid flannel jacket, Western snap-front shirts, fat silver belt buckle, and trademark Resistol Tuff Hedeman cowboy hat. But in this Las Vegas courtroom, the former varsity defensive end appeared uncharacteristically gaunt after 22 months of prison food. Clean-shaven, he was wearing a red prison jumpsuit and plastic orange Crocs, unusual garb for a defendant on trial. But Bundy wasn’t your ordinary defendant.

Among the Bundys’ many acts of resistance was their refusal to don normal clothes for court appearances. Ammon even appeared once in his underwear before a judge after declining to get dressed. The family wanted to show that they were political prisoners, long held without trial even though they had no criminal records.

Indeed, no prosecutor has ever produced evidence that Ammon was armed at Malheur or Bunkerville. Defense attorneys stressed that before the ranch standoff, he’d been a model citizen, deeply religious, with no history of violence. Elected student body president his senior year at Virgin Valley High School, he served two years as a Mormon missionary in Minnesota after graduating. Despite his cowboy garb, Ammon has never been a full-time rancher. His aw-shucks demeanor masks a savvy businessman who, for 21 years, ran a successful fleet-maintenance business he founded near Phoenix. Flight risk? Bundy didn’t even have a passport. His lawyers touted his strong ties to the community, including his marriage to Lisa, his wife of two decades, and six kids, one of them still a baby when he was arrested.

But prosecutors argued that Ammon was dangerous and didn’t recognize the authority of the federal government, and was therefore unlikely to comply with any release conditions set by a federal judge. During Ammon’s two years in pretrial detention, he had resisted even the smallest commands from guards or US Marshals. One of his co-defendants, Pete Santilli, ultimately filed a motion asking to be tried separately from the Bundys because they “have decided it is more important to protest jail procedures they feel violate their rights instead of preparing for a defense in the upcoming case in which they are facing life in prison.”

For his refusal to comply, Ammon spent nearly half of his time behind bars in solitary confinement, including one stretch of 105 days straight. If the government was trying to pressure him to plead guilty, it didn’t work. (“They didn’t know who they were messing with,” co-defendant Eric Parker told me back in 2017.) At the hearing I attended, Judge Navarro noted Ammon’s obstinance. “Are those principles gonna get in the way of him being able to comply with rules and regulations he may not agree with?” she asked his lawyer.

Under oath, Bundy told the judge he was willing to wear an ankle monitor—“I won’t like it, but I will submit to that”—and abide by a curfew. His lawyer then asked him whether he understood that any violation of these conditions could land him back in jail. “If I go against my word, absolutely,” Bundy replied. “It’s a violation of my word to you.” Navarro seemed perplexed. What did he mean, she asked, by going against his word?

“My point, Your Honor, is that I’m giving my word to follow these orders and I take that seriously,” he explained.

From the stand, Ammon projected a messianic quality befitting his namesake, a heroic missionary from the Book of Mormon who, though outnumbered, defends a king’s livestock from bandits and opens the king’s eyes to the Lord. Bundy also seemed remarkably earnest for an alleged domestic terrorist, more like a character in a Jim Harrison novel. Occupiers at the Malheur refuge dubbed him “the prophet,” a reference to LDS church founder (and martyr) Joseph Smith.

As he spoke gravely of honor and duty that day, I had visions of Bundy someday going out in a hail of bullets, laying down his life for the cause of extreme individual freedom. After years of covering Washington politics, especially during the Trump era, I found him principled to a degree rarely seen anymore in American public life. Indeed, I was surprised, sitting on the hard wooden pews of the courtroom gallery, to discover that I kind of liked him.

“Ammon is a different figure of masculinity—a right-wing version of the sensitive man,” writes the poet Anthony McCann, author of Shadowlands: Fear and Freedom at the Oregon Standoff. “His public face is a real-time concern that he has consistently poured forth in every interview, every press conference, every appearance on the witness stand, delivering his payload of sincerity each and every time.”

I’m not the first person to feel a conversion coming on after encountering Bundy. In his book Chosen Country, on the Malheur takeover, James Pogue tells stories of angry Oregon ranchers who would storm the refuge to demand that Bundy leave and instead come out true believers.

Still, I have no illusions about what Bundy has done, and what he and his followers might be capable of. As Aaron Weiss, deputy director of the environmental group Center for Western Priorities, notes, “This is someone who gets his followers killed.” It’s tempting to believe Bundy when he says the Lord protected his family during the Bunkerville standoff, because it’s a small miracle that only cows perished. And someone was killed at Malheur.

More broadly, the Bundys’ intransigence has ignited a new Sagebrush Rebellion that is doing tremendous harm to the cause of public land conservation in the West. They have spurred other armed confrontations with federal land managers and revived efforts by conservative lawmakers in Utah and other states to try to win control over protected federal wilderness areas and fragile desert landscapes that might be exploited for coal or uranium. Such efforts culminated in the Trump administration’s move to downsize Western national monuments and auction off nearby land for oil and gas leasing.

Given the lack of long-term consequences for the Bundys, Malheur and Bunkerville were “dress rehearsals for what we saw on January 6,” said Weiss, who holds a particular contempt for Ammon. Weiss came down with covid just days before he was scheduled to get a vaccine. He was still on oxygen when we spoke in April, and he sees Bundy’s encouragement that his followers resist mask mandates as homicidal. “These are the same groups, the same extremist militias that we saw at Malheur, that we saw at Bunkerville. There’s a straight line from what happened in both Oregon and Nevada to what happened in Washington, DC.”

Ammon Bundy supporter Devin Miller waving a Gadsden flag at Ammon’s gubernatorial campaign kickoff in Meridian, Idaho near Boise on June 19, 2021.

Russel Albert Daniels

One day this past March, Bundy stopped by Josh Thayer’s house in Salem as part of a two-week recruitment tour for People’s Rights. Two dozen or so people were milling about the property when I arrived. None were masked, and most were armed, including an elderly woman with a little six-shooter tucked into the waistband of her Wranglers.

Thayer, a former professional rodeo cowboy who now works in asbestos removal, wore a black cowboy hat, a black coat, and jeans topped with a big silver rodeo belt buckle. Occupying one corner of the yard was a gaggle of Utah Constitutional Militia members sporting their usual camo fatigues and long guns. A couple of girls in the long dowdy dresses favored by polygamists looked on.

Bundy appeared without much fanfare. Clad in his trademark cowboy hat, with his signature Constitution tucked into his shirt pocket, he addressed the small gathering. He had researched the Thayer situation, he said, and consulted the local police chief, as he often does in such cases. “I think, all in all, that tall fences make good neighbors,” he concluded, channeling Robert Frost. Far from urging the crowd to take up arms, Bundy counseled conciliation. “I think there needs to be a good fence, a nice tall one right here,” he told Thayer. “Try to work things out the best you can with the neighbor. I know that might not be what everybody wants to hear, but to be honest with you, I think that’s what needs to happen.”

He pulled some bills out of his pocket. “I got $200 that I’m gonna donate to the beginning of a big fence,” he said, and invited others to contribute. He handed the money to Thayer, who seemed bemused. Then he picked up a stick and scraped a line in the dirt to show Thayer exactly where to build his tall fence. “We were hoping to hear about freedom!” a woman behind me groused. For anyone anticipating the next Battle of Bunkerville, this was a huge disappointment. But Bundy held firm. “I don’t think that’s worth fightin’ about,” he insisted. “I think you just end the dispute.”

The Salem visit offers a glimpse of why Bundy so befuddles law enforcement and environmentalists, why he occasionally infuriates even those who worship him, and perhaps why a federal jury declined to convict him when he seemed so clearly guilty of, well, something. “With Ammon, he’s 100 percent sincere,” says Betsy Gaines Quammen, author of American Zion: Cliven Bundy, God, and Public Lands in the West, who knows Ammon. “And that’s what makes him dangerous.”

His political views, which Shadowlands author McCann described as “cowboy Ayn Randianism,” sometimes lead him to public stances that cost him some followers. “I don’t care about followers,” Bundy told me. A tough stance to take in today’s fringe-politics scene, where followers—on Facebook, at protests, in the voting booth—are the ultimate measure of influence. Bundy’s devotees typically lack his ideological purity. For all their anti-government rhetoric, militia groups like the Oath Keepers tripped over themselves to support Donald Trump and his expansive views of executive power—for their fealty at least 18 members have been charged for their alleged roles, including conspiracy, in the US Capitol violence on January 6.

Ammon didn’t support or vote for Trump. Then again, he was sitting in jail during the 2016 election and never registered to vote in 2020, so that’s hardly a profile in courage. And while some members of People’s Rights encouraged those who wanted to protest in DC on January 6 to bring posters and spread the word about the group, Bundy didn’t go. “I think those people that pushed their way in were confused,” he told me. “I don’t know why people would go waste their time and energy and think that they’re going to somehow influence these people to change their ways and give them freedom. It’s not gonna happen.”

I suggested that the protesters wanted Trump, which is not the same as freedom. After some thought, Bundy agreed. “Yeah, in many ways there was absolutely like a Trump worshipping,” he said. Trump, he said, is a nationalist, and “to me, a nationalist is just one step away from a socialist, a socialist one step away from a communist. None of them recognize that an individual has the rights, that the individual is a sovereign, and that the individual is the one that government is supposed to protect.”

As if to flaunt his own individualism, at a People’s Rights meeting last July, Bundy announced his plans to join a Black Lives Matter march in Boise. He would carry a “LaVoy Finicum” sign in honor of his fallen comrade. The backlash from his supporters, which Bundy anticipated, was fast and furious. Even his brother Mel publicly criticized him for siding with people whom Mel considered rioters and looters. In the end, Bundy didn’t march with protesters—not because of the fallout, he said, but because he refused to wear a mask, which he says is an offense against God.

“We wanted so badly to link arms with him, to have an unarmed libertarian raise a fist with us,” a Black Lives Matter Boise spokesperson told me. “But not wearing a mask is a fundamentally racist act. We were unable to find common ground.” The spokesperson, who did not want to be identified by name, added that many of Bundy’s anti-mask followers had harassed protesters. Bundy is “probably nicer than they are,” he allowed. “Unfortunately, his base are white supremacists. I think he was scared they were going to kill him. He was getting death threats.”

In 2018, Bundy had suffered a similar backlash from his followers after denouncing Trump’s immigration policies. (Bundy, like many LDS members, sympathizes with displaced, persecuted people.) Having spent a lot of his time at Malheur giving whiteboard lessons on the Constitution to locals and militants alike, Bundy thought he could “explain to them why I’d taken those positions and why,” he told BuzzFeed News in 2018. “It’s like being in a room full of people in here, trying to teach, and no one is listening.”

That’s the thing about staunch individualists: Many don’t listen to other individualists. Case in point: On the night of the Salem gathering, Bundy appeared at a larger event in nearby Orem. He stood at the back of the room, where Utah militia members had taken up various security posts. As he waited to speak, Josh Thayer sauntered up, shook Bundy’s hand, and discreetly returned the crisp $100 bills he’d received earlier. He clapped Bundy on the back and said with a laugh, “I’m never gonna build that fence!”

Ammon Bundy on stage at his gubernatorial campaign kickoff in Meridian, Idaho near Boise on June 19, 2021.

Russel Albert Daniels

Ammon Bundy often gets teary as he retells the Bunkerville story. In fact, he chokes up at most public appearances, including in the courtroom. This may seem an unusual display of emotion for someone so rugged. But weeping is viewed as a display of power among Mormon men. (See also: Mitt Romney and Glenn Beck.) As sociologist David Knowlton has written, “Mormonism praises the man who is able to shed tears as a manifestation of spirituality.”

Such was the vibe at Neptuno, a Mexican event center in Orem, just a few miles north of Provo, the spiritual home of the LDS church. I’d followed Bundy’s beat-up RV from Thayer’s house. Upon arrival, I expected armed men in tactical gear to spill out. Instead, Bundy’s entourage consisted of three kids, ages 6 through 14, who seemed to be enjoying their stint as roadies for their dad. They would rendezvous with their mom at the halfway point of Ammon’s tour, where two of their siblings would take their place. Ammon and his wife had already pulled all of them out of school because of mask mandates—everything is a standoff for the Bundy clan. This past October, Ammon showed up maskless at his son’s high school football game and refused to leave. People called the school district and threatened violence. The game was canceled at halftime.

At Neptuno, food stands served tacos and tamales. The vendors were local Mexican families, but Bundy’s audience consisted of 100 or so mostly white folks packed shoulder to shoulder. Some carried signs with anti-vaccine messages.

Bundy started by pulling out his pocket Constitution, a document his family believes is divinely inspired and treats with the reverence of scripture—a belief that American Zion author Quammen calls “theo-Constitutionalism.” This particular Constitution was published by the Idaho-based National Center for Constitutional Studies. The group was founded by the late W. Cleon Skousen, a Mormon anti-Communist crusader and conspiracy theorist whose work provided the intellectual framework for Glenn Beck’s tea party dogma. It was Skousen who popularized the myth that the Constitution doesn’t allow the federal government to own public land of any sort—especially not national parks, forests, or wilderness areas. He also called for the BLM to be abolished.

The Bundys are longtime devotees of Skousen, who is often described as “anti-government.” But that’s not quite right. Skousen worked for the FBI for 11 years and served briefly as the Salt Lake City police chief in the 1950s. He railed against government tyranny, but, like many Mormon prophets before him, believed that Mormons have a sacred duty to protect the Constitution, and saving it is a Manichean battle that might usher in the second coming of Christ. “There’s such a long history of Mormon prophets talking about the religious duty involved in protecting the Constitution,” Quammen said. “I truly believe that Ammon thinks this is his calling, and this distinguishes him from the other anti-government agitators.”

So Bundy wasn’t at Neptuno recruiting soldiers to destroy the government; he was there to restore its integrity. Waving his Skousen Constitution, he hit a sweet spot with the crowd when he condemned the government’s infringement on the right to attend church during the pandemic. These worship restrictions were particularly triggering for the descendants of early Mormons, whom the federal government had persecuted for their faith—one of Bundy’s earliest pandemic protests was sponsoring an Easter service in violation of Idaho’s stay-at-home order.

The audience peppered Bundy with questions about how to reconcile their church meetings with the LDS hierarchy’s admonition to socially distance. “I would have to say that it’s much safer to listen to the promptings of the Holy Spirit, the Holy Ghost, than it is to listen to the precepts of men,” Ammon responded. “In the end, we can stand before God and say I follow what I felt was right and everything else will work itself out.”

Ammon lectured the faithful about the need to uphold the rights expressed in the founding document—by resisting mask mandates and any government attempt to control “what goes in your body.”

“Why do we have to fight the battle of the needle?” he asked, referring to vaccines. “Because we lost the battle of the masks.”

If members of the audience felt that wearing a mask “is against my conscience,” Bundy said, then “not only can you not sit at the front of the bus, you can’t get on the bus! Not only can you not go to college, you can’t send your children to elementary school unless you compromise your beliefs. You are more oppressed than a 1950s Black man…If you think about what’s happening now, it is more oppressive than what happened to the Jews in the 1930s.”

“I can’t wait to see what the media does with those comments,” he said, smiling my way, as the only reporter—and mask-wearer—in attendance.

Like his father, Ammon reveres the civil rights movement even as he grossly misunderstands it. Cliven has compared the Bunkerville standoff to the 1965 march in Selma, although in 2014 he wondered aloud at a press conference whether Black people might have been better off picking cotton as slaves. Nonetheless, Ammon has lifted a page from the civil rights movement’s playbook, adopting its signature tactic of nonviolent civil disobedience, even when everyone around him is armed.

In August 2020, the Idaho legislature held a special session to consider a bill protecting businesses from lawsuits by workers or customers who got covid. The public gallery was closed because of the pandemic, which Bundy saw as a violation of the state’s open-meetings law. On the first day of the session, he led a crowd of armed protesters, who pushed past state troopers into the chamber, breaking a window and yelling, “Let us in!” The confrontation was an eerie foreshadowing of the assault on the US Capitol several months later. The next day, after testifying against the COVID bill, Bundy stuck around the chamber to watch the rest of the proceedings. When state police booted an anti-vax activist from the press area, an outraged Bundy occupied the area himself for several hours, arguing that the law prohibited the exclusion of the public while the legislature was in session.

Instead of letting Bundy cool his jets until he got bored and went home, more than two dozen black-hatted troopers marched into the chamber and arrested him. Bundy went limp, so they had to roll him out in an office chair—more viral video fodder. Officials banned him from the Capitol grounds for a year, but he came back the next day and was arrested again, this time ushered out in a wheelchair.

This past March, Bundy showed up at the Ada County courthouse for his misdemeanor jury trial on Capitol trespassing charges. He refused to wear a mask, so security barred him from the building. Bundy stood placidly outside as his supporters screamed at the cops, who eventually arrested him for failing to appear for court. “I’m not going to assist you in your oppression,” he told an officer who showed him an arrest warrant from the judge.

Bundy finally made it into the courthouse in June, when the state lifted its mask mandates. “Once again the corrupt, crony establishment is attacking me,” he told the Idaho Dispatch. “I have beat them before and I will beat them again with God’s help.” This time, however, God had other plans. His Ada County jury wasted no time in doing what two years and millions of dollars’ worth of federal prosecutions had failed to do: convict him.

“You’re a clever and sophisticated man,” the judge remarked after slapping Bundy with a $750 fine, 48 hours of community service, and three days in jail—with credit for time served. “You have the ability to wield great political power because of the people that believe in you.” Bundy issued a statement accepting the verdict: “The people of Idaho have spoken and I will serve my sentence as ordered.” Two weeks later he asked the judge to throw out the trespassing verdict and acquit him.

Ammon Bundy grilling Bundy burgers with his father, Cliven, at the launch of Ammon’s gubernatorial campaign.

Russel Albert Daniels

Among those who answered Cliven’s distress call in 2014 to help defend the Bundy ranch were Jerad and Amanda Miller, a couple with extreme anti-government and white supremacist views. They were eventually asked to leave the ranch, too radical even for the Bundys. A couple of months later the pair murdered two Las Vegas police officers in a pizza restaurant and put a swastika and a “Don’t Tread on Me” flag over their bodies. They also shot and killed a bystander who tried to intervene before police killed Jerad, and Amanda killed herself. The Bundys decried this violence and tried to distance themselves from the couple.

Some observers fear People’s Rights could foment similar violence, especially because militia groups are overrepresented among its members. Bundy designed the group as a network based on his experience developing a software platform for his fleet management company. He accepts no responsibility for how people might use it—their actions are individual choices that, in his view, have nothing to do with him. “I built tools for people to use,” he said, sounding not unlike a lot of Silicon Valley ceos. “The local people have identified the best people that they think should use those tools. How they use those tools does matter, but I’m not, like, controlling them. It’s a communication tool.”

But Bundy is either oblivious or indifferent to the fact that some people using his tools don’t live up to his moral standards. Take Jeena Nilson, one of People’s Rights’ Utah-area organizers, whom I met in September 2020 at an anti-mask protest in Salt Lake City. As we walked to the governor’s mansion, flanked by Utah Constitutional Militia members directing traffic, she informed me that my mask would make me sick. We also chatted about her anti-abortion activism and her belief that Utah’s then–Republican governor, Gary Herbert, was a socialist. I later discovered that Nilson, a former boys’ gymnastics coach, had spent nearly five years in prison for felony sexual abuse of one of the boys on her team, who was 12 when the abuse started.

Then there’s Sean Anderson, from Idaho People’s Rights. In July, he was sentenced to 18 years in prison after fleeing a traffic stop and engaging in a shootout with police. Anderson had been one of the last occupiers to leave Malheur, where he had made a video telling supporters that if police stopped them en route to the refuge, “kill them.” Two days before he shot at police in Idaho last year, he’d been at a People’s Rights meeting with Bundy, where he lamented feeling oppressed by law enforcement over pandemic restrictions. “I feel out of place in my own country,” he said, vowing never to return to jail. “I’ve made my line in the sand, and I hope God watches over and protects me.”

One of People’s Rights’ crowning achievements took place in January, when the network responded to the call of a member whose 74-year-old mother had refused a covid test when admitted to a Vancouver, Washington, hospital for a urinary tract infection. She was promptly isolated by staff and not allowed to see her daughter. People’s Rights sent out a call to rescue “a patient being held against her will.” Within hours, protesters tried to storm the hospital, forcing a lockdown. Police pepper-sprayed one man, and the woman was eventually wheeled out of the facility with her daughter clutching a pocket Constitution.

Bundy recalls this story in his speeches to highlight “the people’s” successes. What he won’t acknowledge is the potential for an organic protest to become a deadly tragedy. “He’s tapped into a very angry group of people who, like him, think they’re victims,” said the author Quammen. “He told me very clearly, ‘I’m not the conspiracy theory guy, I’m not the QAnon guy.’ But what he is is this guy who is helping with cross-pollination. He’s got the militia people, the anti-vax people, the people who are pro-Trump no matter what—even though he isn’t. These are the guys that Ammon is inspiring. When they hear Ammon talk about being directed by God, when they hear him saying, ‘We’re as oppressed as Rosa Parks,’ I think he is going to get people who truly believe that in rising up against the government, they, like Ammon, are fulfilling a religious duty.”

Bundy’s inspiration, in other words, could lead to confrontations in places like Klamath Falls, Oregon, where a drought has left local farmers competing for water the government has set aside for Native American tribes and endangered suckerfish. Oregon People’s Rights leader BJ Soper, a far-right paramilitary organizer who has been involved in a couple of armed standoffs with the government, has called on militia members to protest the feds’ refusal to open the headgates of an irrigation canal to deliver more water to farmers and ranchers. Bundy visited Klamath Falls in 2020 and has promised to come again if called. “The area in the Klamath river basin is a tinderbox ready to explode,” IREHR’s Devin Burghart told me. “That is the kind of place where Bundy’s intervention could be catastrophic.”

When we spoke, Bundy seemed unconcerned that his organization might foment violence. “To be honest with you, in some ways, I’m worried about violence not being used when it should be used,” he said. “Violence is not necessarily a bad thing when it’s used correctly.”

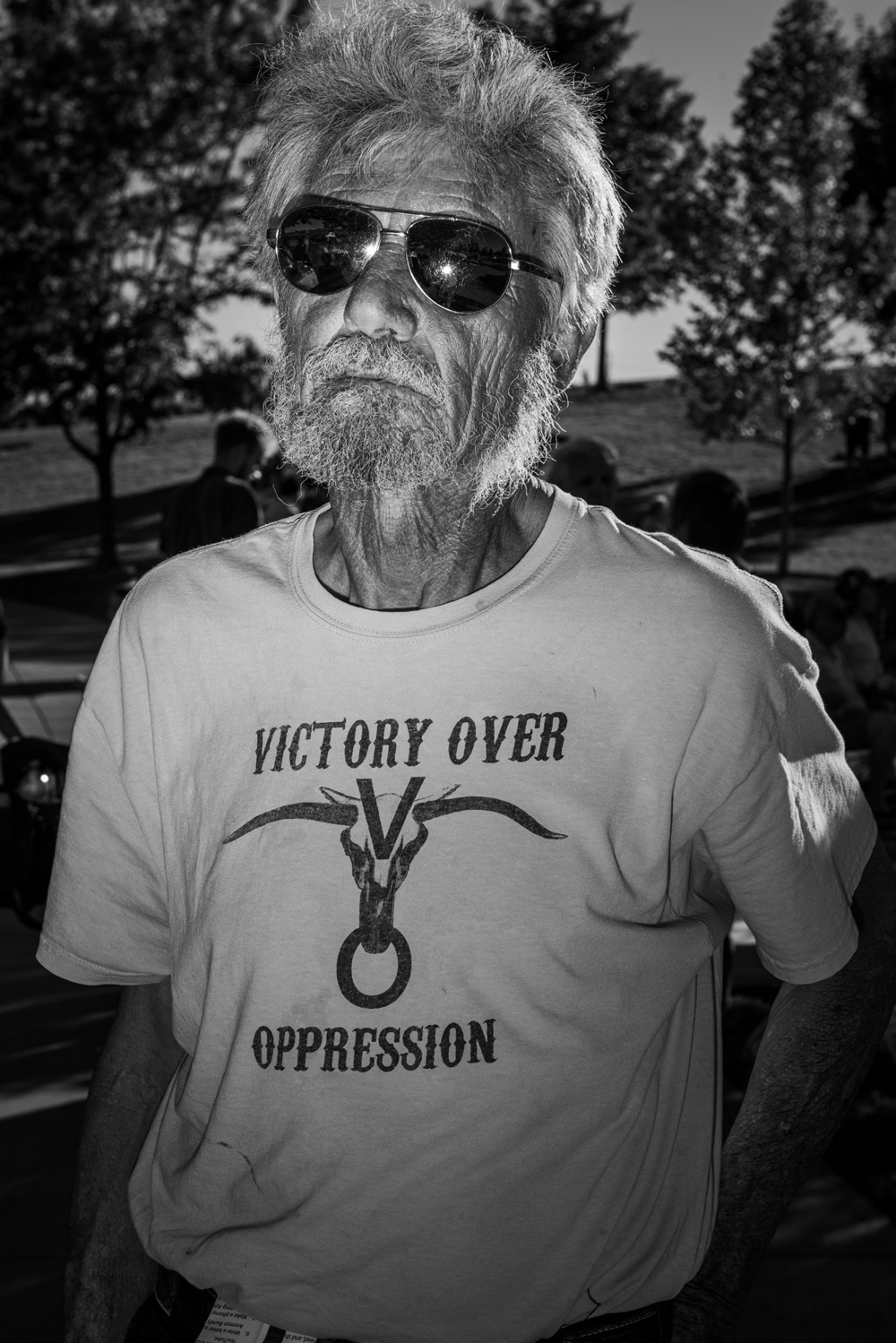

A supporter at Ammon Bundy’s gubernatorial campaign kickoff in Meridian, Idaho near Boise on June 19, 2021.

Russel Albert Daniels

Back in November 2019, Bundy and some militia members rolled into the Peace of Heaven Ranch, in Orofino, Idaho, to stand up for the Nickersons, a family about to be evicted. The family had visions of their ranch becoming the next Ruby Ridge, but when Bundy got there, the local sheriff patiently explained that the Nickersons hadn’t made a mortgage payment in 10 years. Bundy told his followers to stand down. “We feel we have done our due diligence to the family and the matter altogether,” he explained in a video. “If we are wrong, as moral men, we pray that God and the family will forgive us. And now we are going home.”

But the pandemic has revitalized him, providing all sorts of government overreach for him to oppose. In April 2020, for example, he organized an armed protest at the home of a police officer in Meridian, Idaho, who’d arrested a woman for refusing to leave a closed playground with her children. For someone with prophetic visions, such small-bore outrages don’t carry the moral freight of a full-blown civil rights movement, nor would they seem to justify all Bundy has sacrificed, including a successful business and the life of his friend LaVoy. (He now makes a living managing a couple of properties he owns outside of Boise.) He’s not getting rich off his activism or even trying to, as so many far-right activists seem to be. His aura of selfless commitment to the cause is part of his appeal.

I had planned to interview Bundy in Park City, Utah, near the home of a People’s Rights area assistant—an “influencer” who’d been banned for life by Delta Air Lines for refusing to wear a mask. She’d suggested meeting Bundy at a restaurant where people were unlikely to complain about his bare face. By the time I got there, he’d already been thrown out for refusing to wear a mask, so we sat outside in the crisp mountain air and talked as the sun set behind the Wasatch mountains.

I asked him whether spending his time coming to the aid of the Josh Thayers of the world was enough to satisfy his Joseph Smith–level ambitions. “It’s not like I was looking for a cause,” Ammon said. The Bunkerville standoff changed everything. “My cause before was building a business and raising my family and enjoying life. I didn’t need a whole lot more.” And yet, even then, Bundy sensed God had bigger plans for him. About two months later, he filed paperwork to run for governor.

He kicked off his campaign in late June in a park near Boise. Cliven slaughtered one of his government-subsidized cows, and he and Ammon grilled “Bundy burgers,” wearing “I HAD A BEEF WITH BUNDY!” aprons. The event brought together the larger family and some of their most loyal followers. Ammon’s brother Ryan, his stepmother, and, of course, Cliven were all warm-up acts.

Emceeing the event was Diego Rodriguez, pastor of the Christian dominionist Boise Freedom Tabernacle Church and a regular speaker at People’s Rights events. In his introduction, Rodriguez tried to walk back the things that made Bundy seem like a principled, if extremist, iconoclast. Ranting against “fake news,” Rodriguez tried to dispel the notion that Bundy had ever sought common cause with Black Lives Matter, despite video evidence to the contrary. “Ammon is literally the mortal enemy of both BLMs!” he thundered. “That would be like Obama supporting the KKK.”

The podium was flanked by cardboard cutouts of Ronald Reagan and Donald Trump. Bundy appeared carrying a mess of notebooks and papers like some absent-minded cowboy poet. Holding up a legal pad, he explained that these were his journals from the two years he’d been incarcerated. “I tried to write every day,” he said, choking up. The pad was dated from his birthday in September 2017, when he was in solitary. At the time, he said, he and his family were facing a combined minimum prison sentence of 106 years: “The federal government had spent $100 million trying to prosecute us, and our future looked pretty grim…But I felt inspired that day. And I wrote in my journal that ‘at some time, I feel inspired that I should run for governor of the state of Idaho.’ I felt that these thoughts were not my own thoughts, but they were thoughts motivating me, preparing me, and putting in my mind what I should do when the time was right.”

He claimed that the divine instructions were unwelcome. “I looked over them time and time again, wishing the time actually would never come. But ladies and gentlemen, the time has come. And so, I am announcing now that I will be running as governor of the great state of Idaho.”

The Idaho GOP state party chair, Tom Luna, issued a statement before Bundy’s announcement, saying, “Republicans are the party of law and order, and Ammon Bundy is not suited to call himself an Idaho Republican let alone run for Governor of our great state.” Bundy was amused. “The establishment is losing their minds right now,” he said at his campaign kickoff. “I must be really, really scary to these people.”

In fact, Bundy fits right in with today’s Republican Party, offering the perfect blend of extremism and white grievance culture. There’s not a lot of distance separating him from sitting Idaho Lt. Governor Janice McGeachin, a Republican who is also vying for the governor’s office. She has repeatedly aligned herself with the Idaho Three Percenter group founded by Eric Parker—a.k.a. the “Bundy ranch sniper.” She’s expressed solidarity with Todd Engel, a patriot movement hero sentenced to 14 years for taking cover behind a concrete barrier near the Bundy ranch in 2014 and brandishing an AR-15 at federal officers. And she’s fought pandemic restrictions issued by the current, less-extreme Republican Idaho governor, Brad Little.

Bundy’s platform to “Keep Idaho, Idaho” hits on many of the GOP’s favorite issues, including eliminating income and property taxes, reclaiming federal lands for the state, promoting “health freedom,” and turning Idaho into a tax haven. In a Bundy administration, health freedom would not extend to women who want an abortion, which he says he’d ban via executive order on day one. (For all his well-thumbed pocket Constitutions, Bundy seems to have overlooked the fact that if banning abortion were that easy, some Republican governor would have done it by now.) “Given Ammon Bundy’s past, it is not necessarily a bad thing that he is currently spending much of his energy running for office,” said Mark Pitcavage, a senior research fellow at the Anti-Defamation League’s Center on Extremism, “as opposed to engaging in armed standoffs with the government.”

Still, he’s a long-shot candidate. Only a few hundred people showed up for his campaign kickoff, and as of mid-July, he had received only a single, $1,000 campaign contribution. When his brother Ryan ran for governor of Nevada in 2018, he picked up just 1.4 percent of the vote. But Ammon has a deeper following, and the good Lord has helped him overcome impossible odds before. “I’m pretty sure God is not that close an observer of Inland Northwest gubernatorial contests,” quipped Pitcavage.

More to the point: Does running for office make Bundy less dangerous—or more? Pitcavage said it depends on how seriously Bundy takes the race and how much “he’s absorbed the lessons of the past, to recognize what a narrow shave he had before, how close he came to screwing the rest of his life up, and to what extent he might enjoy using this new public platform.”

For now, Bundy’s messianic fervor seems to have found a new target: affordable housing, which he plans to create by taking back public lands from the feds, an ingenious merger of his origin story with a hot-button mainstream campaign issue. After launching his candidacy, he officially stepped away from People’s Rights, throwing himself into the most pedestrian of retail politics. But the state GOP might have reason to worry. “He’s likable in a way folks from the national Republican Party never will be!” Shadowlands’ author McCann told me in an email. “It’s also hard to imagine what else Ammon could do next if he wasn’t just going to go back to his family and his business. How many armed stand-offs does he have left in him?”

A group of supporters at Ammon Bundy’s gubernatorial campaign kickoff in Meridian, Idaho near Boise on June 19, 2021.

When I went to meet Bundy in Park City back in March, drones buzzed overhead and I had a brief moment of paranoia thinking that the FBI was there keeping tabs on him, when in fact they were from the Utah Highway Patrol. He has that effect on people. Sitting outside Billy Blanco’s, we had a wide-ranging conversation about his family and whether Cliven might have had covid (probably). He told me about his childhood, one characterized by hard work on the ranch, but also immense liberty to roam for miles in empty space without adult supervision—a freedom and connection to the landscape he thinks probably shaped his views of government.

It was an amiable chat, and I had to keep wondering whether the man in front of me could really reasonably be considered a domestic terrorist. He just seemed so wholesome, despite some of the truly abhorrent company he keeps. Compared with the last man in politics I had profiled—Florida Rep. Matt Gaetz—Ammon seemed downright saintly and far less dangerous in some ways. I’d definitely rather ride out the apocalypse with Bundy.

Listening to Ammon talk about the way that the Battle of Bunkerville had changed him, I thought about the other forces that had brought him to this point in his life. The simplistic explanation for why the BLM originally tried to push his father and the other Virgin River valley ranchers off public land in the 1990s is that the agency was trying to preserve habitat for the endangered desert tortoise. But the biggest threat to the tortoise wasn’t the feral Bundy cows; it was urban sprawl from Las Vegas. It was easier for the BLM to oust the struggling ranchers than stop the lucrative real estate development that encroaches on wild places and threatens the rural way of life that Bundy represents. You don’t have to be Edward Abbey to feel that loss acutely.

Much of Ammon’s political platform would make this problem worse. He advocates turning public land over to private hands where it could be used for resource extraction—or affordable housing development. Eventually, in Park City, we got cold, and Bundy had another appointment, this time at the influencer’s house. I said goodbye and watched his familiar profile disappear—not mythically riding off into the sunset as he probably would have liked to imagine, but walking across the strip-mall parking lot like the displaced cowboy that he is.