Evicted, Rejected & Locked Out

Mayela Bernal was already struggling to pay rent when she caught COVID-19 in May, which left her hospitalized for a week.

Bernal is a hair stylist who immigrated from Mexico. With the loss of income, her younger child had to take out a loan to pay rent for their Santa Fe apartment.

A friend who was working for Chainbreaker Collective, an economic and environmental justice organization in the city, told her she could get help from the Emergency Rental Assistance Program.

State officials created the application for rental assistance to distribute millions in federal emergency relief dollars to tenants at risk of eviction. The law that created the relief program was passed in December 2020.

Bernal had difficulty collecting all the documents to complete the application, including the lease agreement from her landlord. She said it took her about a week to finish it.

“It’s too confusing for some people who are not able to start the application and finish it in one day—or even for several weeks,” Bernal said through an interpreter. She knows this because she has also been canvassing apartment complexes across Santa Fe with other Chainbreaker members.

Bernal’s experience is far too common.

Interviews with other canvassers show that New Mexico’s application for emergency rent relief is overly complex, requires too many documents, scares undocumented people away from participating and is poorly-translated into Spanish.

Other challenges continue to confront renters as the pandemic stretches on, a Source New Mexico analysis has found, including landlords refusing to accept rental assistance dollars as payment and illegally evicting people from apartments in defiance of state Supreme Court orders and local eviction moratoriums.

Meanwhile, a push to pass a state law protecting renters went nowhere during the last legislative session, though lawmakers, recognizing the state’s housing crisis, vow to try again.

Language barriers

The English version of the rental assistance form is a little unclear, said Cathy Garcia, an organizer with Chainbreaker. For example, the application requires that the person’s physical address match their mailing address, which can be confusing. It also asks how far behind the tenant is on rent but doesn’t specify whether that answer should be measured in months or dollars.

There is a Spanish-language version of the application. But multiple canvassers who speak Spanish said the translation appears to be lifted from Google Translate.

“What state are we living in?” Garcia asked.

Some of the translations lengthen the questions and complicate them, canvasser Yetzali Reyna said.

It’s obvious to Chainbreaker’s Isabel Jurado Herrera that the form was not created by a human, she says, because it’s “a bit too literal.”

She pointed out that many Spanish speakers came here at a young age and did not have an opportunity to complete middle school. The form needs to be translated in a way that more people can understand, she said.

Misgivings about bureaucracy in the politically hostile environment of the US are a factor, too.

2,000 offers rejected

Say you got all the way through the process of applying for the pandemic rent money successfully, despite the language barriers and paperwork requirements. Some landlords still won’t take that money.

Refusing to accept money from the $170 million Emergency Rental Assistance Program undermines the program’s stated goal and is, instead, forcing more people out of their apartments and onto the streets, said state Rep. Andrea Romero, D-Santa Fe.

Landlords either refused emergency relief money or didn’t respond when contacted by the state offering to pay someone’s rent about 2,000 times during the pandemic, according to numbers the Department of Finance and Administration provided to Source New Mexico.

The state is not tracking how many landlords refuse rent or why, said program Director Donnie Quintana. After three contact attempts over seven days, the money is paid instead to the tenant directly, according to DFA, which administers the rent assistance program.

But even though a tenant might get rent money directly from the state program, it doesn’t mean they’ll be able to find housing easily, Romero said—especially if a landlord files for an eviction in court anyway.

“An eviction on their record makes it really hard for them to find other housing,” she said. “So it just kind of snowballs into this very difficult situation.”

Getting money directly also exposes some tenants to heightened scrutiny and, potentially, charges of fraud, according to DFA.

Demonstrators calling for an end to evictions and rent debt listen to a speaker talk through the struggles of living without shelter in Albuquerque. The Party for Socialism and Liberation put together an overnight camp-in about housing rights outside the Metropolitan Court Downtown on Sept. 21. (Marisa Demarco / Source NM/)

DFA has referred about 35 applications from tenants to the state’s Human Services Department for potential fraud investigations, according to spokeswoman Jodi McGinnis-Porter. (About 60% of rent recipients are already receiving some kind of public assistance, according to the state.)

The Human Services Department’s inspector general is “helping DFA understand the tools available with the goal of identifying documents that may be out of the ordinary,” McGinnis-Porter said. None of the investigations have been completed, she said, so she wouldn’t provide more details about why the applications came under scrutiny.

Maria Griego, an attorney with the New Mexico Center on Law and Poverty, said the state should not be putting up more barriers for tenants who need stable housing.

“Now, more than ever, families should have access to rental assistance without the unnecessary red tape, especially given that landlords are often refusing rental assistance in favor of eviction,” she said.

She also pointed out that the federal government is asking states to relax restrictions on the rent assistance money.

Henry Valdez, DFA spokesman, declined to comment on specific fraud referrals. He said every program like New Mexico’s “runs into fraudulent attempts,” which is why he said the investigations are necessary.

As of Oct. 15, state officials said they’d spent spent $54 million of the emergency rental fund and earmarked another $71 million.

Tenants who lost income due to the pandemic are regularly still evicted, even though they qualify for rental assistance. And it’s legal.

Under the law, landlords can evict tenants for reasons other than failure to pay rent. For example, landlords can choose not to renew a lease once it’s expired or cite a way in which the tenant may have violated the lease, Griego said.

But why would a landlord leave thousands of dollars from the state on the table?

For one, it’s a profitable choice amid current market trends, Griego said.

Rising housing prices make it tempting for a landlord to evict a tenant and sell the property, she said, and rising demand for apartments entices landlords to evict a tenant and lease to a new one at a higher rent.

Landlords are also required to fill out tax documents if they receive money from the state, which Griego said might discourage some sketchy property owners.

“We’ve heard from landlords who don’t want to fill (it) out for tax reasons,” Griego said, “which kind of suggests that they’re not reporting all of their income.”

Landlords are required to fill out a “letter of intent” that states they will not evict a tenant if they receive state rent money, though it wasn’t immediately clear how binding that letter is or how long it lasts.

Without responses, DFA doesn’t know if there are common reasons landlords refuse to accept rent money from the relief program.

“We are focused on working with landlords and property management companies that want to participate,” Quintana said.

Landlords reject Section 8 vouchers, too

Cree Walker and her family have a roof over their heads for at least the next couple weeks. If things don’t work out at her extended-stay hotel, she said, it’s hard to see where they’ll find shelter next.

She assumed it would be much easier to find a place. She moved to New Mexico in July from Idaho with her four kids, all under age 12. She carries a Section 8 voucher, which means the federal government will pay most of her rent every month to whichever landlord gives her a place to stay.

Cree Walker, right, and her family have a Section 8 voucher but have been unable since July to find a landlord who will take it. So they have to cram into this extended-stay hotel room and fear being kicked out any day. Pictured are Walker with mom Renae Simonson, along with Walker’s kids Gabriel, 12, Castiel, 7, Azariah, 6, and Renesmee, 5. (Patrick Lohmann / Source NM/)

Walker figured a landlord would welcome the stable income her voucher provides, especially amid a pandemic that has meant many landlords lost rent income and are unable to evict their tenants for failing to pay.

But several landlords rejected her.

“I don’t understand why they’re not willing to take it,” Walker said. “I mean, at least you wouldn’t have somebody that was fired, not able to pay rent and living there for free.”

New Mexico is one of 19 states where it is still legal for landlords to reject a tenant based on how they’re paying rent, be it a Section 8 voucher, a Veterans Affairs benefit or some other subsidy, according to the National Multifamily Housing Council.

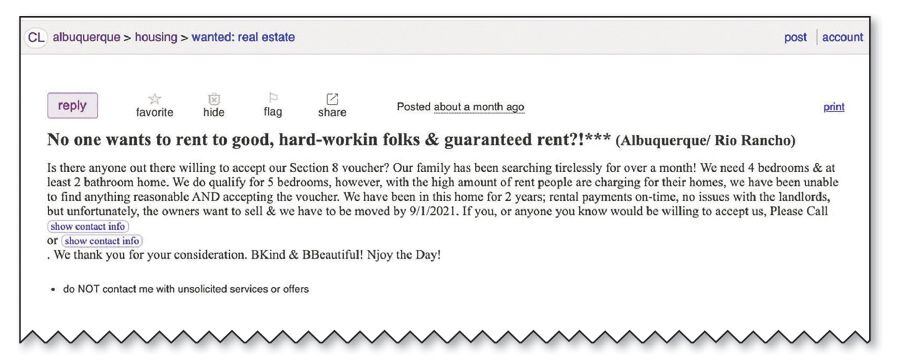

There’s plenty of evidence of what discrimination can look like. Albuquerque and Santa Fe Craigslist pages, for example, feature several ads daily from would-be tenants frustrated that they can’t find a place. They’re often alongside even more ads from landlords of properties where Section 8 is not accepted.

“No one wants to rent to good, hard-workin folks & guaranteed rent?!” someone titled a post on Albuquerque’s site about a month ago. “Is there anyone out there willing to accept our Section 8 voucher? Our family has been searching tirelessly for over a month!”

Until Walker can find a place, she, her disabled mother, her kids and their three dogs are crammed in a room at Siegel Select extended-stay complex in Albuquerque.

They’re struggling to come up with the $300 a week it costs to live there. That is more than many market-rate apartments and way more than she’d pay with her voucher, which limits her obligation to 30% of her income.

Refusing Section 8 is a practice that’s contributing to the state’s housing crisis, Romero said.

“Where can these folks go if they receive a subsidy, but so many landlords refuse to house them because of their status financially?” she asked.

Thrown out anyway

Getting relief money into tenants’ pockets has become even more urgent after the US Supreme Court on Aug. 26 blocked the Biden administration from enforcing the latest federal moratorium on evictions, imposed as a response to the pandemic.

While the federal moratorium is gone, New Mexico still has a statewide moratorium, put in place by the state’s high court.

The City of Santa Fe has an even stronger local moratorium that is tied to the statewide rule. It prohibits landlords from even threatening tenants with eviction for nonpayment of rent. But to enforce it, a tenant must contact local police, who then have to make a report and give it to the city attorney who, in turn, must file a complaint against the landlord.

In the year-plus the local moratorium has been in place, only two tenants with whom Chainbreaker has worked have ever chosen to go that route, Cathy Garcia said. Police do not have any knowledge of tenant law, she said.

New Mexico is one of 19 states where it is still legal for landlords to reject a tenant based on how they’re paying rent. Ads like this one often appear alongside those seeking tenants but who won’t accept Section 8. (Courtesy Craigslist.com/)

None of the eviction bans stops landlords from kicking people out for other reasons, she added. The moratorium never stopped landlords from simply handing tenants a 30-day notice to get out and saying it has nothing to do with paying rent, she said.

Despite the bans on evictions, landlords in New Mexico have filed more than 11,000 eviction notices since the start of the pandemic, according to a Searchlight New Mexico investigation.

Bernal said ongoing evictions in Santa Fe—which has higher rents than 90% of the state—make her motivated to work for reform.

“We have been seeing a lot of cases where there are people that are being evicted from their homes, and they have little kids with them,” Bernal said. “We feel powerless because we can’t do anything to help them, really. It’s sad that people are being evicted, and we want to change that.”

Shadow evictions

Cristobal Sanchez knows what rent day sounds like at Siegel Select.

First, bangs echo down the hall from the manager rapping his knuckles against his neighbors’ apartment doors. Then Sanchez hears him shouting about rent, even if it’s only a few hours late. Then, if the manager is in a bad enough mood, come the threats to call police, to lock someone out or to remove his or her possessions, Sanchez said.

When manager Ali Siddiqui worked his way up the hall to Sanchez’s room last week, his fiancee was in the apartment alone, he said, sleeping and under-dressed. The manager knocked loudly. She scrambled to get her clothes on before Saddiqui used his master key to enter, Sanchez said, to demand rent that was a day late.

“They’re making it very difficult for us to live here,” Sanchez said.

This type of intimidation has occurred at the Siegel extended-stay properties in Albuquerque throughout the pandemic, according to housing attorneys and the New Mexico Attorney General’s Office. It’s also illegal, attorneys say.

And it’s increasing in the city and across the state during the pandemic, advocates agree. As the public health crisis drags on, rental assistance is slow out the door and affordable housing grows more scarce.

Threatening a renter with a lockout or lying about an impending eviction to spur a tenant to leave are what New Mexico state law describes as a “self-help eviction.” It’s an illegal way to coerce someone into giving up an apartment without a court order.

Other examples are turning off electricity, changing locks, removing possessions or barring entry.

These are shadow evictions, occurring without judges, courts or notices. The worst-of-the-worst landlords illegally evict people who have the least support. Housing attorneys say the evictions that occur with a judge’s order are just the tip of the iceberg in New Mexico since the pandemic began.

“In-court evictions are probably the exception rather than the rule,” said Jean Philips, a Gallup-based attorney with New Mexico Legal Aid.

In a brief telephone conversation, Siddiqui referred Source New Mexico’s questions to Siegel Select’s legal department, which did not respond to telephone calls seeking comment for this story.

State law rarely invoked

A state law on the books since 2014 permits tenants who were subject to these illegal lockouts to sue their landlords and get damages or a court order permitting them to re-enter their apartments. But the law is rarely used, attorneys and advocates say.

“I’ve never seen it. I’ve never even heard of it. As far as I’m concerned, it’s like Bigfoot or the Loch Ness monster,” said Garcia from the Chainbreaker Collective.

State statute allows tenants who’ve been illegally kicked out of their apartments to seek several remedies in court, including regaining access to the apartment, collecting damages or erasing all rent incurred during a time someone was denied access to the apartment.

The law defines these illegal evictions as when an owner or manager knowingly threatens, attempts or succeeds in removing a resident from a unit by changing a lock, blocking an entrance, interfering with utilities, removing possessions or making the property uninhabitable.

Chainbreaker Collective canvassers Yetzali Reyna, Cipriana Jurado Herrera, Patricia Aguilar and Mari Aguilar set up a space to help tenants at Evergreen Apartments in Santa Fe apply for emergency rental assistance on Sept. 7. (Austin Fisher / Source NM/)

Using “fraud” is another way to illegally evict someone, according to the law, which often means lying to renters about what the law says to get people to leave an apartment by themselves under false pretenses. That’s what Siegel Select’s conduct amounted to, Griego said.

“Once somebody’s out like that, if they’re locked out, if it’s that sudden, then it just throws people’s lives into chaos,” said Philips, the New Mexico Legal Aid attorney. “And it’s hard just to even keep track of them because of the chaos that results from a lockout.

“So a lot of the time, it’s because people have so much on their plates in that situation, especially if they’ve got kids,” she continued. “Like, I’ll be talking to a client, they’ll be in a McDonald’s parking lot, while their kids are sitting nearby on laptops using the Wi-Fi signal to go to class. Just dealing with the work of being unhoused, they don’t have the bandwidth to file a lawsuit.”

She said the most effective way to solve the problem of illegal lockouts is “a huge investment in community education and empowerment” that would help renters know their rights and stay in their homes even if a landlord tries to bully them out.

A fix, missed

Romero and Rep. Angelica Rubio, D-Las Cruces, sponsored House Bill 111 during this year’s legislative session, a measure that would have made “source-of-income discrimination” illegal. The bill defined “source of income” as Section 8 “or any other form of housing assistance payment or credit, whether or not such income or credit is paid or attributed directly to a landlord and even if such income includes additional federal, state or local requirements.”

It would have prevented landlords from refusing both Section 8 vouchers and rental assistance funds. It also would have prohibited landlords from refusing to renew a lease during a declared public health emergency.

The bill failed in the Senate, which Romero attributed to a packed schedule.

“We’ll keep pushing,” she said. “But we’re hopeful that we’ll see something in the special session to help with this crisis.”

The bill would have also required additional information about a tenant’s rights and next steps on so-called three-day letters, she explained, which inform people of an impending eviction for lack of payment. Receiving those letters doesn’t mean a tenant is immediately evicted. Only a court order can do that.

The bill also would have prohibited landlords from choosing not to renew someone’s lease during a declared national or public health emergency. That was an effort to prevent landlords from skirting moratoriums by evicting people for reasons other than lack of payment, Griego said.

The AG’s Office intervenes as it can, said Matt Baca, the chief lawyer there. Their office saw a “sharp rise” in landlord-tenant complaints during the pandemic, he said. Lawyers there fielded more than 260 of these complaints during the pandemic.

Source New Mexico reviewed about 160 of the complaints made up until February of this year. (The rest were not immediately available from the AG’s office.)

Tenants across the state alleged widespread abuse by landlords, including price-gouging, throwing out property, shutting off electricity, harassment, eviction threats, illegal lockouts and more.

The AG’s office sent a letter to Siegel Select in April 2020 warning the owners to comply with the law. The letter said tenants alleged that managers locked them out, harassed residents and refused to provide replacement keys.

The office sent a second letter to the company in late June 2020, this time regarding an illegal lockout complaint at a second Siegel property in Albuquerque called Siegel Suites. There, a manager turned off electricity to apartment 155, according to a follow-up letter from the AG’s Office to the company.

A tenant who lived there used an electric wheelchair and was “rendered immobile by the manager’s actions,” the office wrote on June 26.

In most of the complaints reviewed by Source New Mexico, the AG’s solution was to send tenants a digital copy of the state renter’s handbook. Officials also called landlords a handful of times and referred tenants to New Mexico Legal Aid in a few other instances.

The attorney general doesn’t represent individual interests, Baca said, so they try to resolve disputes informally by contacting the business. When they get a lot of complaints at once from the same landlord or business, the office issues a cease-and-desist letter and evaluates “for any other available civil enforcement action.”

“We will always provide an impacted person with referrals to legal resources, in cases like these to the Legal Aid landlord-tenant reference materials, and with information on how to contact private counsel,” he said.

But he stopped short of recommending a specific legislative fix to help people impacted by these lockouts.

“With respect to policy reform,” he said, “the Legislature should absolutely look at any reform that will strengthen tenant protections, ensure their rights are protected, and make sure that people can keep access to safe and secure housing.”

The worsening housing crisis has made it clear why House Bill 111 Romero said, so she intends to resurrect it.

It will be up to Gov. Michelle Lujan Grisham whether the issue will be addressed in the legislative session or a special session. A spokeswoman for the governor said the issue is on her radar.

“We’re hoping to put forward an initiative for housing support for the 2022 legislative session, including potentially financing affordable housing efforts—the details of the proposal are still very much in development,” said spokeswoman Nora Meyers Sackett. “As the plan is finalized, we’ll have more information.”

Source New Mexico is an online news outlet launched in late August that offers fresh content daily about how the decisions of elected officials impact people in the state.

Facing eviction?

Apply for emergency rent relief online at RentHelpNM.org

Chainbreaker Collective Eviction Hotline: (505) 577-5481

Know your rights as a tenant

Find affordable housing

Report housing discrimination to the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development: Call 1-800-669-9777 or 1-800-877-8339 or do it online