How Community Organizers and Business Leaders Came Together to Improve Bedford-Stuyvesant

When Senator Robert F. Kennedy paid his first visit to Bedford-Stuyvesant in February of 1966, my mother and sister still lived there, and I was living just a few blocks outside the neighborhood with my wife and son. I was deeply connected to that part of Central Brooklyn, which would always feel like home to me. Kennedy and his staff had made it fairly clear that they were serious about initiating their broad-based development program in New York City, and Harlem and Bedford-Stuyvesant were the two neighborhoods that they were exploring.

Until the beginning of the 1950s, Bedford-Stuyvesant was a racially and economically mixed community, and one that I knew well. I had been born and raised there; played punchball in the streets, basketball in the playgrounds; and attended neighborhood public schools from first grade through junior high school. By 1960, the community had grown to the size of a small city, and its population of more than four hundred thousand people had shifted from 75 percent white to 85 percent African American and Latino.

When the racial balance changed from predominantly white to predominantly people of color, it became increasingly difficult for local residents and businesses to get credit. Most banks stopped making loans or granting mortgages to African American residents, which meant they were forced to pay exorbitant rates to mortgage brokers and as often as not to take out a second mortgage. At the same time, real estate speculators frightened many white families into selling their houses at fire-sale prices, houses they then resold or rented to African American buyers at spectacular profits to themselves. The new owners had to then turn to the mortgage brokers, and became trapped in the credit cycle.

Unable to get affordable credit, existing homeowners were hard pressed to keep up with necessary maintenance and repairs to their properties. Many let out rooms to help cover mortgage payments and other basic expenses, a practice which led to severe overcrowding. Conditions in the neighborhood deteriorated, exacerbated by a decline in public services—garbage collection, police, education, healthcare. By 1960, incomes had fallen, unemployment was high, and so was the teenage high school dropout rate.

The politics at work were complicated and the key players were opinionated and tenacious—with good reason.Following serious riots in Harlem and Bedford-Stuyvesant in July of 1964, the Central Brooklyn Coordinating Council (CBCC), a robust network of civic groups and political organizations, commissioned the Pratt Institute’s Planning Department to survey the area’s problems and possibilities and come up with a plan for rehabilitation. The Pratt study described 10.5 percent of the housing units in the twelve-block survey area as “in a dilapidated condition,” and another 28.5 percent as “seriously deteriorating” and in need of “immediate attention.”

The study also found a high rate of owner-occupancy—22.5 percent of the buildings were owner-occupied and another 9.7 percent were owned by individuals who lived ‘in close proximity’”—and identified that homeowners lived in the area an average of fifteen years. This suggested the existence of a stable, middle-class base in the community that could potentially provide leadership for reform.

When Senator Kennedy arrived in Bedford-Stuyvesant on that winter afternoon in February, his visit was big news, but he was greeted by community leaders who were cynical at best. The politics at work were complicated and the key players were opinionated and tenacious—with good reason. Kennedy wasn’t the first to show interest in Bedford Stuyvesant. Others had taken notice of the community and vowed to help, but there was little to show for it.

The New York Times story reporting his February 5th visit was titled “Brooklyn Negroes Harass Kennedy,” and it reported that the senator “toured dilapidated Bedford-Stuyvesant buildings yesterday and found himself the focus of wrathful comments by leaders of the heavily Negro Brooklyn section.” In addition to describing the various stops made and the contentious meeting that took place at the Bedford Avenue YMCA to conclude the visit, the piece detailed the skepticism, even anger, of the community activists, most of whom were leaders in the CBCC.

It quoted Ruth Goring, who was assistant to Brooklyn Borough president Abe Stark, as saying, “You know what, I’m tired, Mr. Kennedy. We’ve got to have something concrete now, not tomorrow, yesterday.” Even Elsie Richardson, another strong, strategic woman organizer active in the CBCC at the time, who led the tour as chairwoman of the Urban Planning Committee, admitted that she’d almost withdrawn the invitation. “What, another tour?” she told the senator’s office. “Are we to be punished by being forced again to look at what we look at all the time? We’ve been studied to death.”

Hundreds showed up to the YMCA to hear Kennedy and to express their strongly held views. They were open to his good intentions, but had been disappointed by woefully inadequate anti-poverty initiatives too many times to stay silent. Also, the situation was more urgent than ever, with crime, poverty, and unemployment at their highest rates and growing.

It was a tense meeting for the senator by all accounts, and perhaps he underestimated the strong reaction he would receive. One of his biographers quotes him as telling an aide the next day, “I don’t have to take that shit. I could be smoking a cigar in Palm Beach.” But the senator wasn’t put off. He left Brooklyn feeling challenged and inspired and soon announced that Bedford-Stuyvesant would be the home of his revitalization initiative.

The community leaders whom Kennedy and his team met, and tousled with, may have been frustrated, but they were also passionate and committed.Tom Johnston, executive assistant to Senator Kennedy, later explained why Kennedy and his team chose Bedford-Stuyvesant. To begin with, he said, the second largest concentration of Black people in the country was in Central Brooklyn. Only the South Side of Chicago was bigger. “But beyond that,” Johnston said, “we found that the community people we were working with were… much more interested, it seemed to us, and much more willing to work together for the community, than say, people in Harlem, to take the other example.” Johnston also referred to the neighborhood’s better housing stock as playing an important role in fostering a greater sense of community. The community leaders whom Kennedy and his team met, and tousled with, may have been frustrated, but they were also passionate and committed, and it was clear they would be fierce allies in the fight for urban renewal.

From the beginning, Kennedy and the team he assembled were committed to addressing the underlying problems in urban centers from a development focus. They wanted to look at the community as a whole—its jobs, its housing, its education system, its arts, its culture, and its recreation—and combine community action with the private enterprise system to make change. Kennedy was interested in working with the community to put together a comprehensive plan, and he was willing and able to enlist the brightest business minds around to help. It would be a social mission that would use the best business practices to accomplish its goals. The result was the establishment of the first community development corporation in the country.

I was still working for the NYPD when I’d first heard about Kennedy’s efforts in Bedford-Stuyvesant. I believe it was an article in the Amsterdam News in December of 1966 that alerted me to the fact that Kennedy had come to Bedford-Stuyvesant, along with Senator Jacob Javits, New York City mayor John Lindsay, and Under Secretary of the Department of Housing and Urban Development Robert Wood, to announce the formation of a new development corporation created to revitalize Bedford-Stuyvesant. It was actually two corporations—one representing the community and made up of community leaders, to facilitate housing rehabilitation projects, job training, education, health services, and education; and the other made up of prominent business leaders, to provide fiscal and managerial leadership and attract capital and businesses to the area.

Kennedy made his announcement to a crowd of about a thousand people during a CBCC community development conference, held at P.S. 305 on Monroe Street. He was adamant that the success of the initiative depended on it having roots in the community, and he was critical of programs that were imposed from the outside, where members of the community did not have a stake. He also acknowledged that he sounded like a Republican since he was advocating for private assistance, rather than governmental action, but he defended his approach, which he said was a very sensible way to rehabilitate poverty-stricken neighborhoods. And Kennedy had managed to gain support for the effort from Republicans, many of whom were not big fans of the Kennedys and were not necessarily people who might have imagined themselves leading efforts to fight urban poverty.

When the initial announcement was made on December 10th, Kennedy had already recruited Thomas Jones, a civil court judge with a history of political involvement in Bedford-Stuyvesant, to lead the board of the community corporation, which would be called the Bedford-Stuyvesant Renewal and Rehabilitation Corporation (R&R, for short), as well as a group of active community leaders, including Elise Richardson, Lucille Rose, Oliver Ramsey, and Don Benjamin, who very much wanted this new initiative sot succeed.

Kennedy had also assembled an impressive group of leaders for the business corporation, which would be called the Development and Services Corporation (D&S), including former Secretary of the Treasury C. Douglas Dillon, William Paley of CBS, Andre Mayer of Lazard Freres & Co., and Thomas Watson of IBM. He had also managed to get a significant investment, $750,000, from the Ford Foundation. Within a few months, Benno Schmidt of J.H. Whitney & Co. and George Moore of First National City Bank would also join. The senator had for the first time, as he’d hoped, brought together a city government, private foundations, the federal government, the private sector, and a community to work together on a groundbreaking urban revitalization project during a time when cities across the U.S. were struggling.

Kennedy’s association with Bedford-Stuyvesant made people pay attention to it in a way they hadn’t before.I was intrigued by Kennedy’s innovative idea that you could bring the most successful for-profit thinkers into an arena with community people to collaborate about how best to address major societal issues, and he was doing it in my own backyard. Here you had a man who many thought was next in line for the presidency of the United States, choosing to focus on Bedford-Stuyvesant as a place where he could make a necessary and demonstrable difference. Kennedy’s association with Bedford-Stuyvesant made people pay attention to it in a way they hadn’t before. He’d already built an unlikely coalition of major business leaders and seasoned political activists, and started to raise capital.

That was the extent of my knowledge and interest when my phone rang a few weeks later and Earl Graves was on the other end. Graves, who went on to do many things, including becoming an extremely successful media entrepreneur, at the time as the only African American on Kennedy’s staff, and also a Bedford-Stuyvesant native. Earl and I had grown up together in Bedford-Stuyvesant.

We’d played together when we were kids of eleven or twelve years old, and he was a member of the Boy Scouts’ drum and bugle corps when I’d led it. He’d called to invite me to come and meet with Senator Kennedy, whom I’d met once before, very briefly—basically a hello and a handshake—during an official police department ceremony at the Statue of Liberty. Earl also spent some time trying to persuade me to take an active interest in the Bedford-Stuyvesant project.

I was immersed in my work when Kennedy’s people came calling. It was a fascinating, but tense, time in New York and my position as deputy commissioner for the NYPD, which I’d had for a little over a year, kept me busy and challenged. The idea of a new job was the farthest thing from my mind, but I was fascinated by Kennedy’s initiative, and I feared Bedford-Stuyvesant was in danger of self-destructing if something constructive wasn’t put into place soon. I agreed to meet with the senator.

Kennedy’s Manhattan apartment, where we met, overlooked the United Nations. When I walked in and was introduced, it seemed like there was a long period of silence, but the senator then quickly got right to the heart of the matter telling me that he was undertaking an important effort in Bedford-Stuyvesant. He talked about his vision and how important he thought it would be not only for the community but for the country. He also talked about giving people more say in what was happening to them. “Have you read about it?” he asked. I said that I had. “I’ve been told,” he replied, and “I agree, that we need you to work with us on it.” He then asked if I’d be willing to meet with Tom Jones, the chairman designate of R&R, who he said was personally interested in the project succeeding and personally interested in having me involved.

It was a brief meeting as meetings go, but he was serious in his purpose, and it was clear pretty quickly that we had a point of connection, in the way that you just do with some people. It was flattering to have him tell me that I had something he felt could be important to the success of the Bedford-Stuyvesant project. A specific job hadn’t bene named, but it was implicit that they were looking for an operating head, and although I wasn’t looking for a new job, I remained intrigued enough to meet with Tom Jones a couple of days later.

Jones had apparently been briefed pretty well—by Earl Graves, I assume—and he, like Graves and Kennedy, emphasized what a tremendous opportunity this initiative represented for Bedford-Stuyvesant and how much was riding on its success. We talked at great length about my background and what I’d been doing, and he stressed that it would take a very serious—or as he called it, professional—person to realize the potential of this position, and that he was determined to hold out for the right person, no matter what pressure might be exerted from others in the organization. He also indicated that, from everything he’d heard and seen on paper, he thought I was that kind of person.

I wasn’t certain that it would turn out to be anything more than a great announcement that died.When Jones asked if I’d meet with his personnel committee, I agreed, but I wasn’t sure I’d be willing to take on the job were it off red. For one thing, once I’d had the chance to learn more about the basic design of the program, which at that point was still pretty thin, I worried that it was high on purpose and objectives, but awfully short on methodology and resources. I wasn’t certain that it would turn out to be anything more than a great announcement that died, not for lack of motive or intent, but for lack of deep and cohesive support. Jones also expressed some concern about the personnel committee having other candidates, and his particular unease about their top candidate’s ability to carry out the job.

Tensions were running high within R&R at the time, and that was no surprise. There were strong factions forming within the organization, struggles over the appointment of an executive director, and an uneasy alliance with D&S, the business corporation, who the community group already felt was acting without input from them.

My meeting with the personnel committee was scheduled to take place in a small storefront office on Fulton Street between Nostrand and Bedford Avenues. In those days when you worked in the police department, they both protected and controlled you to such an extent that drivers were assigned to you twenty-four hours a day and you had to fight to get away from them.

Some people look at a car and driver as a great benefit. To me, it often felt like a burden as it required constant communication and a significant compromise in independence. In any event, as I was driven to Bedford-Stuyvesant that day, I remember driving past the boarded-up, abandoned buildings on Fulton Street, surveying the vast landscape of urban decay, and thinking how much improvement was necessary, and would be possible, with a serious and well-supported renewal effort.

I arrived about ten minutes before the scheduled meeting time and waited for an hour for the committee to assemble.

__________________________________

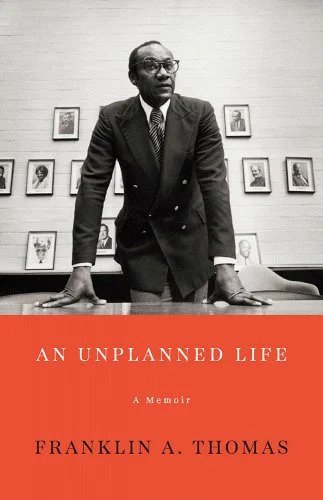

Excerpted from An Unplanned Life: A Memoir by Franklin A. Thomas. Copyright © 2022. Available from The New Press.